Democracy as Musical Chairs

In New York City, where I live, two senior New York representatives in the US House—both Democrats, both powerful and influential, will face off in an unexpected primary in August. There’s nothing wrong with some competition. Indeed, that holds particularly true for those most deeply entrenched in government. Still, it did not and does not have to be this way.

Congressmembers Maloney (chair of the House Oversight Committee) and Nadler (chair of the House Judiciary) must fight for their respective survival in a newly drawn 12th district because New York courts (in a surprise decision) rejected the state’s redistricting maps. Even more fundamentally, though, they must fight because New York lost a seat in the reapportionment of congressional representatives that followed the 2020 census.

I’ll say it again:

It did not have to be this way.

It does not have to be this way.

Let me show you what I mean: Consider this gif, which looks like the cover of my book, but is in fact a data visualization.

Keep your eye on the letter “a” in the upper right hand corner.

Notice how long that "a" is either blue or gray. Whenever it is blue, that means that New York state (which it represents) gained a seat in the US House after a census. That was true for NY following these censuses: 1790, 1800, 1810, 1820, 1830, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, and 1930. For 1890, the "a" turns gray because NY kept the same number of seats in the House of Representatives after that census. NY's "a" turns red for 1840-1860, a consequence of an abandoned attempt to limit the House's growth. In 1920, Congress failed to reapportion, and so every state's letter is gray in the visualization.

From 1940 on, the "a" turns red and stays that way as New York lost seats in every successive apportionment. While that took place, the population of New York rose from 12,587,967 in 1930 to 20,215,751 in 2020. Despite having nearly twice as many people to represent, the state's delegation in Congress shrunk from 45 to 26.

The result has been growing Congressional districts, decreasing the likelihood that a representative will know and attend to their constituents. As Ross Barkan explains, in reference to the mid-twentieth-century experience of one of New York’s most influential House members, the long-serving Emmanuel Celler: “Celler’s career reflected this reality; he went from representing two neighborhoods to parts of two boroughs.”

This is not a peculiar injustice plaguing New York. It’s an entirely ordinary scandal. It happens all the time.

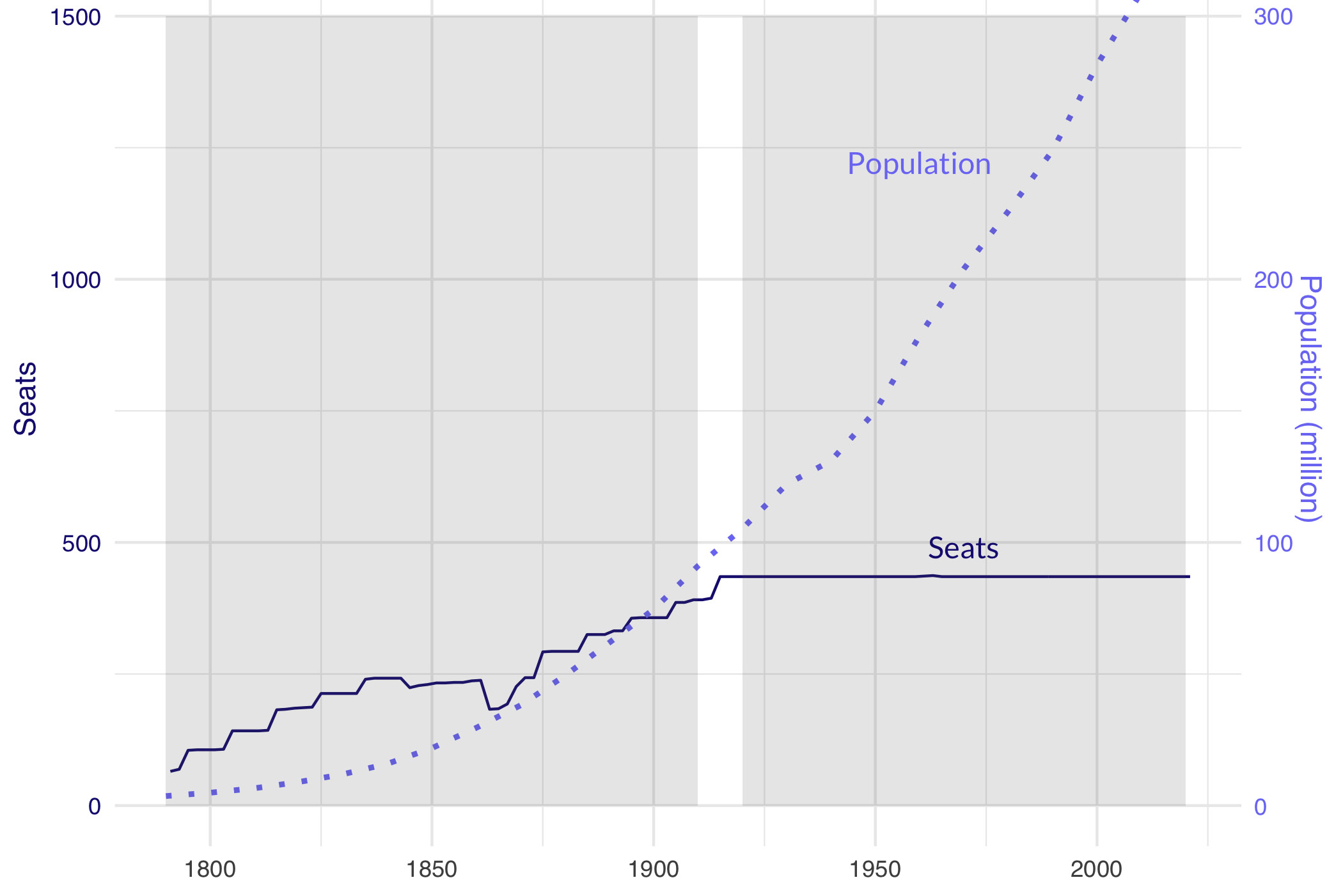

That’s because the size of the House has been frozen for a century while the entire population has tripled. The divorce of population growth from the size of the people’s branch of government stands out in this graph, designed by Kevin Ackermann and Taylor Savell for USapportionment.org.

The number of people represented by each member of Congress was in the vicinity of 30,000 when the nation was founded. By the time the House reached 435 seats, that number had risen past 200,000. Now, each representative must speak for over 700,000 constituents.

Now, take another look at the visualization.

It illustrates the results of every apportionment 1790 to 2020. To begin with, each decade passes at a stately pace in the visualization. Each of the 50 colored-in letters is coded to correspond with one state. Their placement accords, roughly, with US geography. A series of blue letters representing new states and their new representatives tracks the westward expansion of the United States. For the first half of US history, blue and gray letters abound. Congress received the results of the census in those first hundred years, deliberated and debated, and usually ended up increasing the size of the House. Then, in 1920, powerful figures in Congress decided to break tradition and hold the House steady in size. They accidentally broke the apportionment process instead. No apportionment happened, and so: all the letters turn gray.

What follows, a brilliant dance of colors, is actually the frenetic shifting of seats that followed as Congress installed an automated apportionment system. Democracy became a strange cousin to musical chairs. The number of players kept growing, but the places to sit stagnated.

Credit: Robin Sloan, Dan Bouk, and William Bouk, using data compiled by Taylor Savell and Nora Ma

Credit: Robin Sloan, Dan Bouk, and William Bouk, using data compiled by Taylor Savell and Nora Ma

There is no reason we have to play this perverse game, denying ourselves representation.

At the end of 2021, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences made the case for enlarging the House in an important and compelling bipartisan report, by Lee Drutman, Jonathan D. Cohen, Yuval Levin, and Norman J. Ornstein. The authors make the case that the House’s size was once frozen on grounds of increasing its efficiency. But a House stuck at 435 seats has not proven itself efficient. In fact, they write: “Even before the budgetary and administrative growth that surely lies in the federal government’s future, at its current size, Congress can barely handle all of its duties.”(15)

The report argues for an immediate addition of 149 seats, to make up in part for the long period of stasis, followed by a return to older traditions of House expansion: “Going forward, the House should continue to expand as the population grows. Specifically, Congress should endeavor to increase by the number of seats necessary to ensure that no state loses a representative, as used to be the norm (while also adding additional seats as needed to ensure that the House has an odd number of total seats.) This number is not the same as the number of seats that shifted between states.”(18) The authors insist that “Americans, especially those who live in states with growing populations, should not periodically lose representation in Washington.”(18)

Democracy should not devolve into a game of musical chairs.

READ MORE:

- Pre-order Democracy’s Data (out August 23, 2022)

- watch: Danielle Allen, “Our Common Purpose” 26 February 2021

- Geoffrey Skelley, “How the House Got Stuck at 435 Seats,” FiveThirtyEight 12 August 2021

- Editorial Board, “America Needs a Bigger House,” New York Times 9 November 2018

- James Fallows, “We’re Stuck with the Senate. What Then?” Breaking the News 11 December 2021