The Thrill of the Chase

“This is so much fun.”

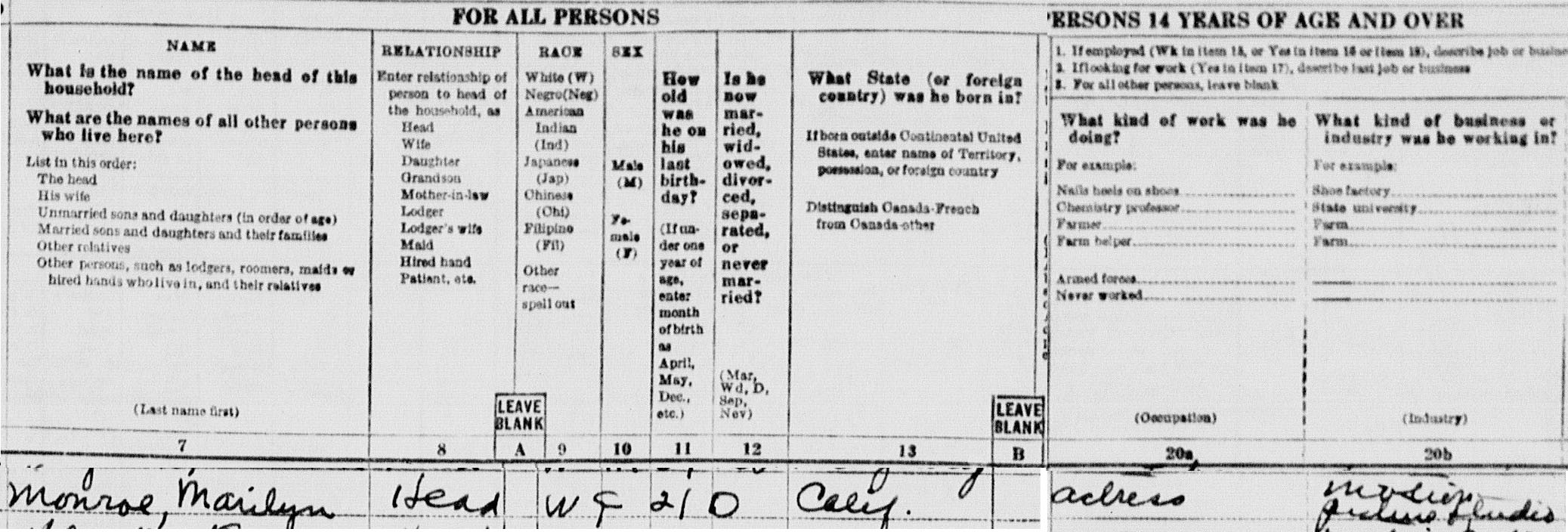

That was the message I got from Ashley Tourtelot, a student researcher in my history lab at Colgate. She had just found Marilyn Monroe in the 1950 census records. (Beverly Hills Township, LA County, CA, E.D. 19-216, sheet 77)

I couldn’t disagree. I, too, could not stop searching through the recently revealed records.

It really was fun.

It was fun to find a person.

Some of the fun had to do with the particular people we were looking for. Like a paparazzo hiding in a bush at a celebrity home, I (or Ashley or you) could go snooping in the census and catch a famous person at an unguarded moment.

Some of the fun stemmed from the time-travel that historical research so often makes possible. Looking at census record, it feels like you are somehow closer to the person represented. It feels like you’re there with them, or close by, and the intimacy across decades is powerful.

There is also the jarring way that a standard set of categories make extraordinary people look ordinary. Monroe in 1950 was on the brink of becoming a superstar—that year her name appeared on the census, but it also appeared on a new contract with Fox studios, leading in coming years to films like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes or Niagara. Still, for the census taker, Monroe was just another “actress” in the industry “motion picture studio.” To the government, Monroe was one among many, as neighboring entries on the census sheet make clear.

I wonder if that is what Monroe was for Margaret Bell Reid, her enumerator. Did Reid know this famous actress? Did she know that the woman she listed as Marilyn Monroe would have appeared in the 1930 and 1940 censuses as Norma Jean Baker? When Reid placed a “D” in the twelfth column indicating this young woman had already been married and divorced, she couldn’t have known the full story, unless Monroe offered up more than the census demanded, adding “My relationship with him was basically insecure from the first night I spent alone with him,” which is what she wrote in her private notes, revealed in 2010.

Did Reid, a 52-year-old Idaho transplant, realize that Monroe had lowballed her own age? For the official records, the nearly-24-year-old actor would be 21. Sure: census records were supposed to be confidential, but people talked, and I’d guess Monroe had a reputation (and maybe a working age?) to uphold.

(One of my favorite tidbits I learned when writing about the history of social security was that labor leaders pushed against incorporating birth year in social security numbers. They knew that age discrimination was real and they wanted to protect the potential for workers to lie to employers, while telling the truth to the government’s actuaries.)

So, all of that is surely fun. The greatest part of the fun, though, is the chase. When there’s just the right amount of difficulty, when the records make you work for it.

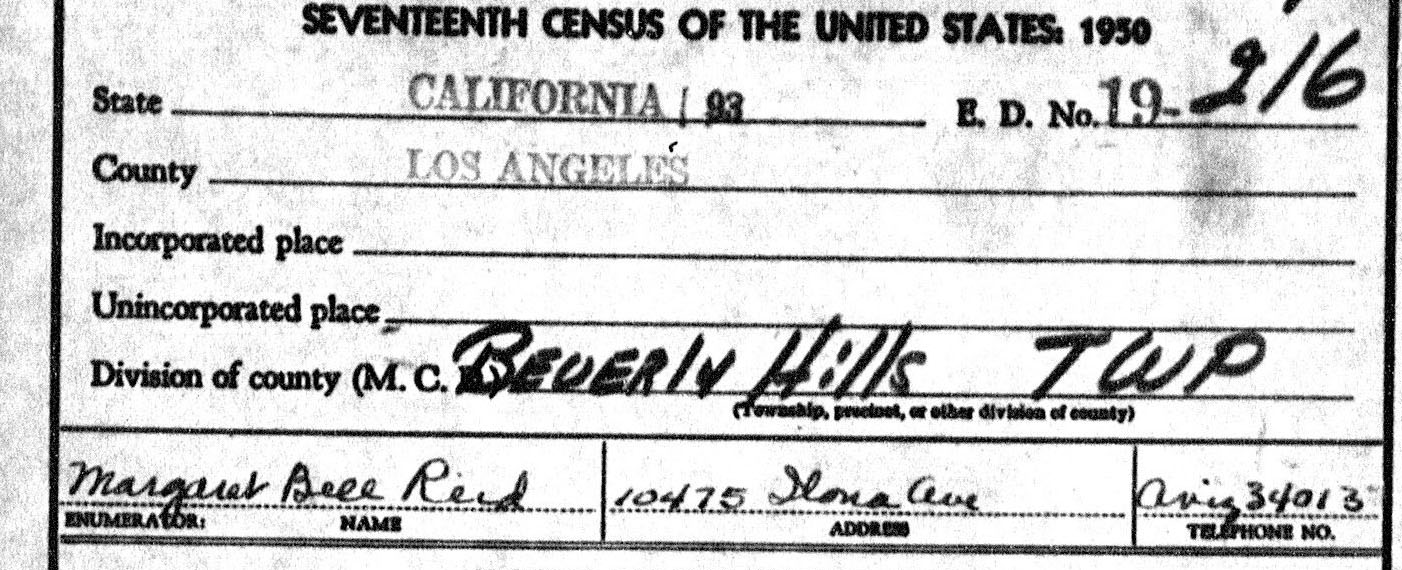

Finding Monroe’s enumerator, for instance, proved to be quite the challenge. I knew her home address because it appeared on the first page of the folder she used to take the census: She lived at 10475 Ilona Ave.

Figuring out which enumeration districts encompassed Ilona Ave required paging through a lot of census maps. Thankfully, Ilona Ave was a short street and I was able to guess (with the help of Google Maps) that Reid’s home fell within E.D. 66-842, just over the border with Beverly Hills.

From there, it was just a matter of reading all of the entries in the district. I found Ilona Ave first, and then on the next page, the entry for Reid and her family.

“The chase” and its “thrills” evoke a hunt, or (possibly) romance. If the latter, then we are working in a rich (and troubled) tradition of professional history. According to historian Bonnie G. Smith, in one of my all-time favorite essays about history, the men of the late nineteenth century who founded seminars and centered archival research in state papers also spoke obsessively and romantically about the documents they sought. “[Leopold von] Ranke’s characterization of his archival research as driven by ‘desire’ and ‘lust’ invoked the fundamental truth of sex” writes Smith, “while his metaphors of princesses and virgins sheltered him in pure love.” (124) Desires to hold or protect or possess fueled the historian’s long hours of plodding through papers, while the researcher also proved his masculinity by suppressing all those desires, turning them instead toward the production of objective knowledge.

It is hard to argue that we’ve entirely escaped these older resonances, as here we are looking for a sex symbol in state archives.

Marilyn Monroe wasn’t our first lab discovery that day. In fact, Ashley had taken the lead earlier in an effort (suggested by lab member Jose Trinidad) to find the family behind the Wonder Woman comics.

The Marstons were hardly celebrities—they were no Marilyn Monroe. But Ashley and Jose knew who they were, as would many thousands of readers of Jill Lepore’s Secret History of Wonder Woman or the even larger audience of the film it inspired, Professor Marston and the Wonder Woman.

In her book, Lepore draws on Marston family papers (and clues in Wonder Woman comics) to recreate a messy complicated family, involving the voluble, beloved, and frequently failing (or flailing) patriarch William Moulton Marston and his first wife, Elizabeth, as well as two later lovers: Olive Byrne and Marjorie Wilkes Huntley. Eventually a small gaggle of children followed too. The book explores the dynamics of this polyamorous household and the stories that its members told to conceal the truth, or–at least–to seem a bit less scandalous or queer.

Jose wanted to know how the Marstons made themselves sensible to the census taker. So did the rest of us. The chase was on.

We all began at the National Archives’s search gateway, typing in Marston family names. An optical character recognition system trained to read handwriting has made a first pass through all of the names in the entire 1950 census. The results are spotty, but considering how hard it is to read handwriting, spotty results are spectacular. In this case, though, the automated system left us without answers. Our searches turned up nothing.

How could we find the family?

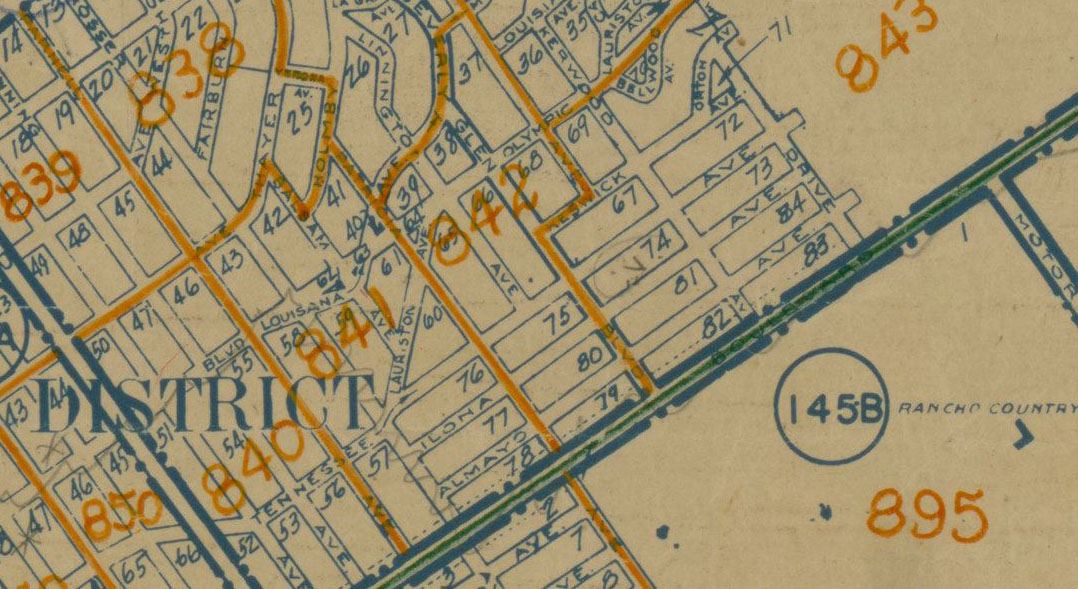

It turned out, Jose and Ashley weren’t the first people in our lab to wonder about the Marstons. A few years ago I went looking for them (successfully) amongst the 1940 census sheets. As a result, I knew where they lived: 81 Oakland Beach Avenue in Rye Village, Westchester County, NY.

With that address, we could sift through census maps from Westchester County that were originally created to tell each enumerator where to go to ask their questions. The National Archives interface makes this a little tricky. Not all maps from Westchester County show up in one place. (You won’t find the right maps in the “ED Maps” section here, for instance.) So we had to scroll through the Westchester EDs, looking through descriptions that mentioned Rye, which only surfaced 13 pages of results later, with the ED map here. Those maps narrowed down our search and made E.D. 60-326 look like the most likely site for the Marstons’ house.

A few minutes later, Ashley announced: “I’ve found them.”

We cheered.

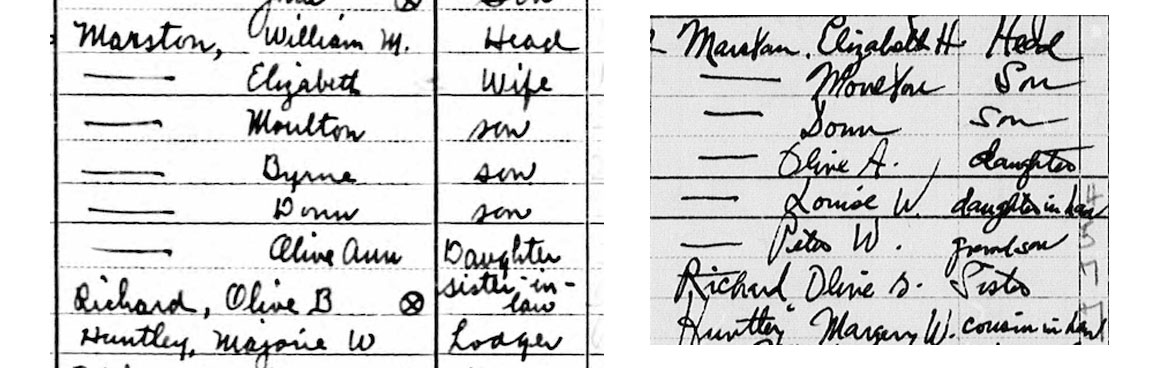

Setting the 1940 census records for the Marston family next to their 1950 data, it is clear that things have changed. William Moulton Marston no longer appears on the census. He has died and Elizabeth, whose steady work as a researcher at Metropolitan Life made her the longtime family breadwinner, assumed the status of household “head.” Just as Lepore had told us, the rest of family stuck together: Olive and Marjorie remained with Elizabeth; they were family.

Olive got the enumerator to write down “sister-in-law” in 1940. That changed to “sister” in 1950. This could suggest a consistent storyline, that Olive and Elizabeth were biological sisters. When William had been “head,” that made Olive an in-law, but now with Elizabeth graduating to the top of the household, Olive shifted to simply “sister.” I emphasize that this could be what happened. Given how little control people had over what enumerators wrote and how much variation and error appears in a census sheet, the shift from sister-in-law to sister could also be chance.

Marjorie Huntley’s shift in status from “lodger” to “cousin in law” is harder to explain. Cousin in law?? Maybe Marjorie told the enumerator a story like this: I was the cousin to Elizabeth’s recently departed husband. Maybe not. The change, though, results in distinct shift in status: where Marjorie had previously been someone related through commerce (as a lodger), she became in 1950 a part of the (extended) family.

It is part of the charm of the census records that they hold on to many secrets and maintain their mysteries. Even once the chase is won, our prizes are new questions to ask and new problems to puzzle over.