The Powerful Numbers Primer

Last Wednesday, Data & Society released A PRIMER ON POWERFUL NUMBERS, a reading list that makes an argument. I wrote it over the course of a the last year with Kevin Ackermann and danah boyd.

Here’s the extraordinary, beautiful cover, from artist and designer Andrea Carrillo Iglesias—she also designed the beautiful interior!

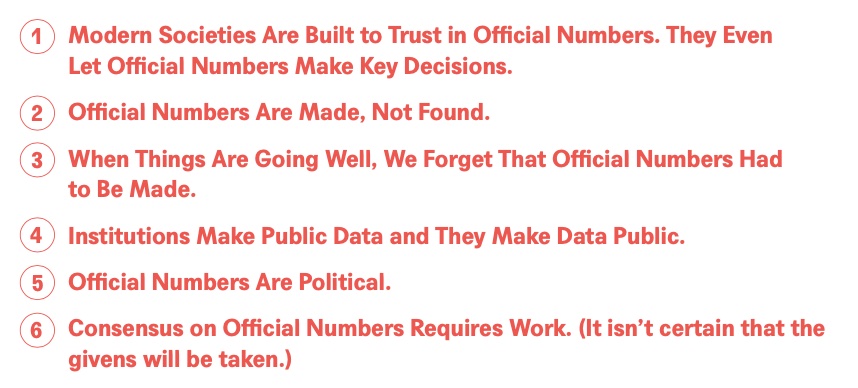

The primer is organized around six arguments. Each argument builds on 3-5 books or articles, listed in a “Get Started Reading” section. Then it’s followed by a “Read More” section filled with texts that informed the preceding explanation of the argument.

Nearly every text we listed could also have fit in another argument reasonably well. They’re all so closely related.

Already, we’ve heard from people who are using the primer in their classrooms or from data science people who can find new contexts and meaning for their work through it. (This is both a surprise and very gratifying.) Nick Seaver, whose Computing Taste: Algorithms and the Makers of Music Recommendation I recently pre-ordered, made this request on twitter:

Being hip, as I am, first, I googled “TIA.” Then, as you see, I politely declined the request.

The thing is that this was a really rewarding exercise—certainly for me, but I think for Kevin and danah too. In one of the earliest drafts, Kevin and I had been working for a while and had put together many words, quite a bit of history and context, and a long list of books. (We had funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation to work on this.) I had recently written a short entry on “quantification” for this really terrific—and hefty!—reference work, Information: A Historical Companion, but I also wished that I could share something that was outside a paywall or wasn’t bound in cloth. Then danah cracked the code (or the nut?): we needed to turn our descriptions into arguments.

Reader: this wasn’t what I wanted to hear at the time. Like many (all?) writers: I wanted to hear that it was perfect as it was. (That must be a universal sentiment for bloggers, right?)

We learned a lot as we worked out how best to make those arguments, argued amongst ourselves and with colleagues, and settled where we settled. My desire, or hope, is that our readers (including many students) will be drawn in. I want them to like it and to enjoy the experience of reading and thinking with it. But then I also hope that they will argue with and about these claims, and so make them better.

In the end, I have to admit that the making of this primer has been both more fun than I expected and has taught me more than I ever anticipated. If it becomes a means for readers to teach me things too, then—on a personal level—it will have been very rewarding. So, it is mildly tempting to agree to Nick’s facetious request. Send me your primer requests!!

On the other hand, writing a primer like this is a big responsibility. I think we often felt the weight that came with canon-making, canon-asserting—or the weight of claiming someone else’s arguments and work to be part of a project that you are defining. That’s a weight all instructors feel when putting together a syllabus, but this was to be a far more public syllabus than I had ever prepared—and it also had to stand on its own.

The day after our primer came out, a sociologist named Victoria Reyes published “For a Du Boisian economic sociology.” In the piece, Reyes joins a call made by others to more fully make race a constitutive category for economic sociology, but she also insists that the right way forward cannot be simply to push for the same researchers to turn to new questions. To better incorporate race in economic sociology (as an institutionalized field) will require acknowledging (and inviting in) all those scholars, past and present, who have already been studying race and the way it shapes economic life. They should be welcomed into the fold, their work recognized (and sometimes granted awards), and their research questions should help to redefine the larger field. The more general point that I took away (as someone who admires econ soc, but wouldn’t call myself an economic sociologist) is this: if we want our scholarship to be more inclusive or decolonial or anti-racist, that will require allowing our entire fields to be changed.

Reading that, I thought again about the aspirations of our primer and its failings. We had done our best to make race a central category in our own thinking about the social study of quantification. In doing that, I had confronted by own past category errors. My first book failed to site Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s wonderful The Condemnation of Blackness, in part because I had filed it away as a book about “race” and not a book about “statistics.” When I read it a couple years ago, I was profoundly embarrassed: it was both, and it was, in fact, a really important book about statistics. (I think it was a syllabus by Will Deringer that first alerted me to my error.) I apologized for the oversight on twitter.

I hope that future critiques of this primer will challenge it and us for how we’ve defined the field.

For sure, we will deserve any flak we get for the primer’s narrow geographical focus. It is very Anglo-American, and even then very, very USA-centric. That’s unfortunate, especially now when scholars from “around the globe (presently Europe, North and South America, and Africa)” have gathered to launch a new Society for the Social Sciences of Quantification. I haven’t yet been able to attend the society’s seminar series, but I hope to soon.

And I’ll look forward to the day when we, or someone else, publishes an even better, more expansive, hopefully field-bending primer.